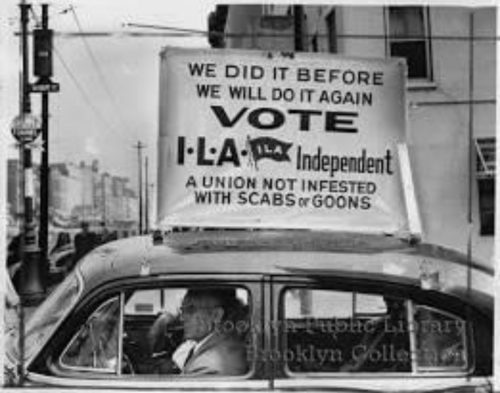

Circa 1950s: A member of ILA local 1814 out of Brooklyn, NY is campaigning for the ILA during the upcoming election against The International Brotherhood of Longshoremen. At the time the IBL wanted to take over the ILA. In a very close election the ILA defeated the IBL to remain the bargaining agent.

The following excerpt about the ILA and IBL election was taken from the History link on this website where you can read other great stories from our past:

1950 TEDDY GLEASON FIGHTS TO SAVE ILA…

- ILA IN TURMOIL

- The IBL Threat

- National Labor Relations Board

- ILA Victorious in Port of NY

- IBL Violence

- Teddy Gleason Fights to Save ILA

- Demise of the IBL

To combat the spread of the carpetbag IBL, the ILA sent Thomas “Teddy” Gleason, ILA General Organizer, from port to port nationwide. The urgency of the task was matched by Gleason’s unremitting ardor. Meanwhile, 17,000 longshoremen voted in the December 23rd and 24th 1953 National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) election to determine representation in the Port of New York. The ILA was victorious, but immediately, Governor Dewey waged a campaign to overturn the election results.

“Many ILA officials could not simply stand by as their men fought on the docks and risked punishment to join the fight.”

Tension on the New York piers was mounting daily. Staunch ILA loyalists and many other longshormen were at best suspicious and at worst intolerant of the IBL, which they viewed as a machine of the Waterfront Commission and a scab union. By early March 1954, the storm finally hit when Teamster boss David Beck betrayed the ILA by refusing to cross an IBL picket line. News spread and on piers up and down Manhattan, ILA longshoremen refused to touch Teamster deliveries. The cry, “To hell with these scabs, lets hit the bricks” crippled the Port of New York as gangs of longshoremen walked off the docks in a wildcat strike, which spread like wildfire.

A March 4th NLRB injunction forbade ILA leaders from striking or disrupting freight transportation. Many ILA officials could not simply stand by as their men fought on the docks and risked punishment to join the fight. Violence erupted by mid-March as the IBL, facilitated by the police and Beck’s Teamsters, smashed picket line after picket line. On March 18th the NLRB examiner effectively overturned the December elections based on the claim they were conducted “in an atmosphere of terror, coercion, and intimidation.” despite evidence to the contrary. This proved to be the last straw, for less than a week later, Bradley made the ILA strike official. Other unions and workers gave their complete support to the ILA, including a major Teamsters local, which indicated Beck’s opposition to the ILA strikers was not shared throughout the rest of the Teamsters.

The balance of power began to shift as Gleason gained ground against the IBL and longshoremen along the coast refused to handle diverted cargo. Dewey’s anti-ILA entourage responded to the shift with a series of legal actions. Then, on April 4th the NLRB officially set aside the results of the December elections and called for a new vote. The final blow, however, was the NLRB’s announcement that the ILA would be banned from future elections unless it ended the work stoppage “forthwith.” Bradley had no choice but to send his men back to work.

The ILA won a slim victory in the May 26th election, despite aggressive IBL campaigning. In August 1954, the results were finally approved and certified by NLRB and the ILA was given representational rights in the Port of New York. The IBL did not go quietly and forced a third representational election in 1956, in which it was again defeated. By the time an AFL-CIO committee recommended re-admittance for the ILA in August 1959, the IBL was active only in the Great Lakes. In October, the IBL officially dissolved itself and IBL president Larry Long became president of ILA’s Great Lakes District.