Overview of ILA History

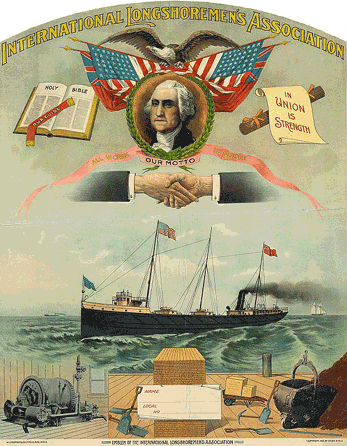

When Port of Baltimore native and International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) leader Jeff Davis coined the phrase “ILA: means ‘I Love America'” during World War I, he explicitly connected the ILA with a deep and passionate patriotism, which has been a defining characteristic of the Union since its infancy in America’s heartland straight through to today’s era of advanced internationalism. ILA patriotism runs deeper than the personal convictions of the Union’s dynamic leaders – it is an expression of the central role longshoring has played in this nation’s history.

1500 THE ROOTS OF THE ILA

Origin of the Term “Longshoreman”

Mercantilist Exploitation

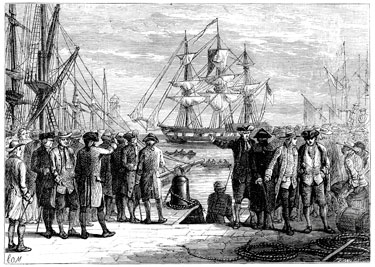

The roots of the International Longshoremen’s Association lie deep in the history of colonial America when the arrival of each new ship bearing goods from the Old World was greeted with cries for “Men ‘long shore!” The longshoremen who rushed up to the ships were colonists, normally engaged in any number of full-time occupations. In the first hard years of life in this country, they left their occupations freely to unload the anxiously awaited, sometimes desperately needed, supplies without pay. As the new land began to develop a fledgling economy, and the ships were too many to count, the men were drawn to the shores by the extra money they could earn stevedoring precious cargo on and off the ships.

As the nation matured, European imperialism gave birth to exploitative mercantilist trade practices. Land was no longer cheap or easy to be get, and many new immigrants congregated in the cities, hoping to find work amid the bustle, especially along the coast, where the bulk of the growing country’s business was still being done. The number of professional longshoremen grew by thousands.

1800 THE DAWN OF UNIONISM

Exploitation of Workers The First Longshoremen’s Union

By the early 19th century, the longshoreman of the day eked out a meager existence along the North Atlantic coast. Their working conditions were wretched and their wages pitiful. Many were new to the country and unfamiliar with the customs and language. Exploitation was the order of the day. But an unseen change was being wrought in the souls of these good men. The day was coming when none but they themselves would be the masters of their destinies.

“It wasn’t until 1864 that the first modern longshoremen’s union was formed in the port of New York.”

By mid-century, the longshoremen had begun to organize. We know this from various historical documents that tell of work stoppages and the creation of worker benevolent associations; a primitive form of unionism was gradually coming into existence. Nevertheless, resistance to this change was strong, and it wasn’t until 1864 that the first modern longshoremen’s union was formed in the port of New York; the Longshoremen’s Union Protective Association (LUPA).

1870 THE FIRST LONGSHOREMEN’S UNION IS FORMED

The Dawn of Unionism

Exploitation of Workers

The First Longshoremen’s Union

By the early 19th century, the longshoreman of the day eked out a meager existence along the North Atlantic coast. Their working conditions were wretched and their wages pitiful. Many were new to the country and unfamiliar with the customs and language. Exploitation was the order of the day. But an unseen change was being wrought in the souls of these good men. The day was coming when none but they themselves would be the masters of their destinies.

“It wasn’t until 1864 that the first modern longshoremen’s union was formed in the port of New York.”

By mid-century, the longshoremen had begun to organize. We know this from various historical documents that tell of work stoppages and the creation of worker benevolent associations; a primitive form of unionism was gradually coming into existence. Nevertheless, resistance to this change was strong, and it wasn’t until 1864 that the first modern longshoremen’s union was formed in the port of New York; the Longshoremen’s Union Protective Association (LUPA).

1880 THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ILA

The Lumber Handlers

Dan Keefe

During the time when the major unions of the late 19th century were battling themselves into near extinction in the North Atlantic, a new union was taking shape on the banks of the Great Lakes. It was here, in 1877, that an Irish tugboat worker from Chicago named Dan Keefe formed the first local of the Association of Lumber Handlers, later to be known as the International Longshoremen’s Association.

“Dan Keefe formed the first local of the Association of Lumber Handlers.”

That Keefe was successful in his endeavors to establish such a union on “The Lakes” is truly impressive and is a monument to his skill as an organizer and leader among men. From the outset, Keefe faced significant challenges, most notably the outright hostility to unions of Chicago’s influential industrialists and the traditional anti-union leanings of longshore recruits from small Midwestern towns. Nevertheless, Keefe successfully expanded membership in the newborn union to include large numbers of dockworkers. His ability to accomplish what so few union leaders in the past had been able to do-make good on promises to improve working conditions and wages – quickly attracted new members to the union.

1880 EARLY THREATS TO UNIONS

Big Business Exploits Racial Strife

Union Breaking

The late 19th century was a time of great economic upheaval which saw periods of alomost full employment and union expansion followed by depression, lower wages, and intense competition for jobs. There were bitter divisions among the Irish immigrants and their “non-white” counterparts (“non-white” is the derogatory term then used to refer to Italian and Southern Mediterranean immigrants). These divisions were to some extent esacerbated and often exploited by big business seeking to turn the unions against themselves. Various unions, such as LUPA and the Knights of Labor, competed with one another, and weak labor leadership was unable to resist increasingly powerful and invincible big business.

” These divisions were to some extent esacerbated and often exploited by big business”

Unions were broken. LUPA was disbanded before the turn of the century. But the survivors fought back. There were countless wildcat and/or organized work stoppages resulting in violence and massive losses in wages. Between 1881 and 1905 there were more than 30,000 strikes.

1880 REALISM AND CAUTION

The Haymarket Riot

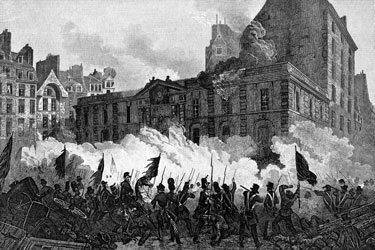

ILA’s early success owes much to Dan Keefe’s leadership style. Keefe was a powerful leader who believed in almost absolute authority. His decisions were informed by realism and caution, the absence of which had been the downfall of countless labor leaders before him. Maude Russell, an historian of the ILA, characterized Keefe as being not heroic, but often proven right by history.

“The victorious industrialists crushed union after union in Chicago, but Keefe’s longshoremen withstood their attacks and grew stronger.”

Perhaps the clearest example of Keefe’s cautious approach to thorny situations is his refusal to become involved in the Eight-Hour Day movement, which ended in the bloody Haymarket Riot of 1886. The victorious industrialists crushed union after union in Chicago, but Keefe’s longshoremen withstood their attacks and grew stronger.

1880 THE HAYMARKET RIOT

A violent confrontation between strikers and police at McCormick Reaper Works, an industrial plant in Chicago, on May 3, 1886. During the fighting, some police and protesters were injured by gunfire. The event led German-born anarchist labor leaders to call for a protest rally the following day, during which more workers gathered at Haymarket Square to express their disapproval of the violence the previous day. As police again arrived and attempted to disperse the crowd an unknown person threw a bomb which killed seven officers and injured many other policemen and bystanders. Eight anarchists were arrested for the crime, seven of whom were sentenced to death and one to life in prison. By 1887, four of those convicted were hanged, one had committed suicide and two of the remaining three were given reduced prison terms. In 1893 the three remaining men were pardoned and released by Illinois governor John P. Altgeld who claimed there was not enough evidence to connect them to the crime.

1890 CREATION OF THE ILA & AFFILIATION WITH AFL-CIO

AFL Affiliation

Lake Carriers Association

In 1892 delegates from eleven (11) ports convened in Detroit where they adopted the by-laws of the longshoremen’s Chicago local and the name National Longshoremen’s Association of The United States. By 1895, the name was changed to International Longshoremen’s Association to reflect the growing numbers of Canadian members. Shortly thereafter, the ILA affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

” In the end, the ILA was almost alone on the Lakes. Once again, caution and common sense had led ILA unharmed through a virtual firestorm. “

As the turn of the century loomed, the ILA had approximately 50,000 members, almost all on the Great Lakes. By 1905, membership had doubled to 100,000, half of which were scattered throughout the rest of the country. ILA leaders focused on eliminating independent stevedoring firms and securing closed shop contracts. Keefe bargained with employers, guaranteeing uninterrupted work in return for badly needed improvements in working conditions and wage increases.

Keefe resigned in 1908 and T.V. O’Connor, another Great Lakes tugboat man, became the ILA’s new president. O’Connor’s presidency spanned twelve of the ILA’s most intriguing and influential years. In 1909 a bitter three-year strike on the Great Lakes pitted the employers’ Lake Carriers’ Association against every maritime union except the ILA, whose locals wisely voted against participation because it was clear to them from the beginning that the strike was a losing battle. So powerful and well equipped was the Lake Carriers’ Association that Lakes shipping ran almost regularly despite the union walk out. In the end, the ILA was almost alone on the Lakes. Once again, caution and common sense had led ILA unharmed through a virtual firestorm.

1900 STRUGGLE AND CHANGES

FIGHTING COMMUNISM AND RACISM

Port of New York

Clayton Anti Trust Act of 1914

ILA Absorbs LUPA

Gangland Myths

For longshoremen nationwide, and especially for those in the Port of New York, this was an era of great contradiction, where landmark legal advances to protect the rights and safety of workers stood in stark contrast to the actual conditions for longshoremen. The United States was the only country with a large foreign commerce without any laws to protect the safety of its longshoremen. Even the celebrated Clayton Anti Trust Act of 1914, which legalized strikes, boycotts, and peaceful picketing did little to improve actual working conditions for longshoremen.

“It is true that some elements-encouraged by the laws of supply and demand-engaged in illicit behavior, but never to the extent that first Hollywood and later the press would have the public believe.”

The 1914 absorption of LUPA into the ILA prompted the creation of ILA’s New York District Council and ignited an intense period of growth for the union both in terms of size and power. The organization of coastwise longshoremen in 1916 was a significant victory that greatly improved the ILA’s position at bargaining tables-shippers no longer had the option of diverting freight from striking ports along the Atlantic.

As the ILA grew, power shifted increasingly to the Port of New York, where the branch headquarters for the International were established. There, a young man named Joseph Ryan was furiously organizing longshoremen while rising through the ranks to become an officer of the New York District Council and in 1918, president of the Atlantic Coast District.

In 1921, the frenzied pace of longshoring during World War I slackened and ILA president T.V. O’Connor resigned. Anthony Chlopek, the last of the Great Lakes presidents, was elected ILA International president and Ryan served as his First Vice president for the six years of Chlopek’s presidency. Perhaps the most significant development during Chlopek’s term was the institution of the Prohibition Enforcement Law. In direct contrast to its desired effect, Prohibition actually had a demoralizing, corrupting effect on society. Despite fictitious portrayals of gangland capers unfolding on the waterfront, the true state of affairs on New York’s piers never even remotely approached the elaborate plots designed in the artists’ minds. It is true that some elements-encouraged by the laws of supply and demand-engaged in illicit behavior, but never to the extent that first Hollywood and later the press would have the public believe.

1900 ILA ARRIVES IN NEW YORK & ABSORBS LUPA ILA MEMBERSHIP GROWS

Opposition to the “Wobblies”

Fighting Gulf Coast Racism

ILA Arrives in Port of New York

While the Lakes were pitched into turmoil, ILA locals were cropping up across the U.S. and Canada, with 307 locals in good standing by 1911-242 on the Great Lakes, thirty-four (34) on the Gulf coast, sixteen (16) on the Atlantic coast, seven (7) on the Pacific coast, and even six (6) in Puerto Rico. This extraordinary national expansion marked the end of the dominating influence of the Great Lakes locals on the union. Under O’Connor, the ILA Gulf Coast and Pacific Coast Districts were established, in 1911 and 1912/3(?) respectively. Though this was a period of overall growth for the union, the power and presence of the ILA in many ports expanded and contracted from time to time due to a number of outside factors, including economics and politics, as well as inter- and intra-union clashes.

“The ILA … set up some of the most socially and politically aware labor organizations of the day.”

The ILA successfully staved off the communist “Wobblies” in Baltimore and Philadelphia, the old-time Knights of Labor in Boston, and the unenlightened racists of the Gulf coast to set up some of the most socially and politically aware labor organizations of the day. However, nowhere was the ILA’s expansion to have more of a lasting influence on the union than its arrival in the Port of New York.

In May 1908 ILA Local 791 became the first branch in the Port of New York to survive past infancy, despite a dire need for organization. By 1914, less than ¼ of New York’s dockworkers were in unions, roughly divided between the ILA and LUPA.

1920 GANGLAND MYTHS

STRUGGLE AND CHANGES

Port of New York

Clayton Anti Trust Act of 1914

ILA Absorbs LUPA

Gangland Myths

For longshoremen nationwide, and especially for those in the Port of New York, this was an era of great contradiction, where landmark legal advances to protect the rights and safety of workers stood in stark contrast to the actual conditions for longshoremen. The United States was the only country with a large foreign commerce without any laws to protect the safety of its longshoremen. Even the celebrated Clayton Anti Trust Act of 1914, which legalized strikes, boycotts, and peaceful picketing did little to improve actual working conditions for longshoremen.

“It is true that some elements-encouraged by the laws of supply and demand-engaged in illicit behavior, but never to the extent that first Hollywood and later the press would have the public believe.”

The 1914 absorption of LUPA into the ILA prompted the creation of ILA’s New York District Council and ignited an intense period of growth for the union both in terms of size and power. The organization of coastwise longshoremen in 1916 was a significant victory that greatly improved the ILA’s position at bargaining tables-shippers no longer had the option of diverting freight from striking ports along the Atlantic.

As the ILA grew, power shifted increasingly to the Port of New York, where the branch headquarters for the International were established. There, a young man named Joseph Ryan was furiously organizing longshoremen while rising through the ranks to become an officer of the New York District Council and in 1918, president of the Atlantic Coast District.

In 1921, the frenzied pace of longshoring during World War I slackened and ILA president T.V. O’Connor resigned. Anthony Chlopek, the last of the Great Lakes presidents, was elected ILA International president and Ryan served as his First Vice president for the six years of Chlopek’s presidency. Perhaps the most significant development during Chlopek’s term was the institution of the Prohibition Enforcement Law. In direct contrast to its desired effect, Prohibition actually had a demoralizing, corrupting effect on society. Despite fictitious portrayals of gangland capers unfolding on the waterfront, the true state of affairs on New York’s piers never even remotely approached the elaborate plots designed in the artists’ minds. It is true that some elements-encouraged by the laws of supply and demand-engaged in illicit behavior, but never to the extent that first Hollywood and later the press would have the public believe.

1920 THE WAGNER ACT & PACIFIC COAST SPLIT

DEPRESSION AND WAR

The New Deal

Wagner Act

Communist Infiltration

Pacific Coast Split

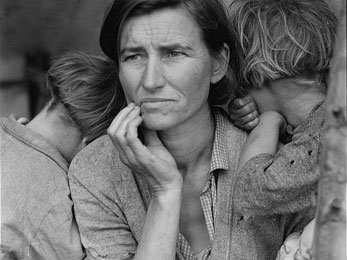

Ryan was elected International president in 1927. Under his leadership, the ILA weathered more than its fair share of ups and downs. During the Great Depression, the ILA nearly drowned as masses of unemployed workers flooded the market with cheap labor and company unions flourished. Then, encouraged by passage of New Deal legislation limiting the use of injunctions to prevent strikes and picketing (Norris-LaGuardia Act) and guaranteeing the rights of workers to vote for their own representation (Wagner Act of 1935), the union immediately began reorganizing and reclaiming lost ports.

“Following the war, the ILA was at its peak, with wages and membership up.”

Through tireless efforts, Ryan and the union’s regional and local leaders regained much of the lost ground, but often at the cost of diminished centralization. Nonetheless, membership again soared, increasing as much as six-fold in as many years in some districts. But the process of rebuilding was not without hurdles, and significantly, Communist infiltration of the ILA’s Pacific Coast District lead to the unsuccessful 98-day Maritime Strike and consequent departure of Pacific coast longshoremen from the ILA.

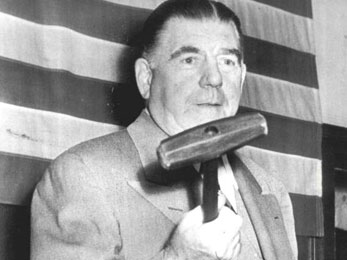

The spirit of rebirth continued as World War II created a commercial boom. Following the war, the ILA was at its peak, with wages and membership up. Ryan was elected “Lifetime President,” an honorary title reflecting his stature and prominence in the union. Unfortunately for Ryan and the ILA, the union’s toughest battle loomed in the near future.

1950 ILA ACCUSED OF GANGSTERISM

ILA Accused of Gangsterism

Gangland Myth Sensationalized by Media

ILA President Ryan Discredited

AFL Turns Against the ILA

The 1950s was a decade of turmoil and trauma for the ILA. Several sensationalist articles printed in New York City newspapers focused on so-called rampant gangsterism on the City’s waterfront. At the same time, increasing unrest on the New York waterfront caused by internal conflicts in the ILA resulted in a 25-day work stoppage that halted only when New York State Industrial Commissioner Edward Corsi appointed a board of inquiry to investigate the October 1951 agreement in question. Extending the investigation beyond its original mandate, the Corsi Report first addressed the voting procedures initially at question-which turned out to be flawed, but not fraudulent-and then went on to focus on irregularities in the administration of several New York locals.

“Following the war, the ILA was at its peak, with wages and membership up.”

The Corsi Report captured the attention of the public-it was perfect ammunition for the press-as well as that of Governor Thomas E. Dewey, who ordered his New York State Crime Commission to conduct a full investigation of the ILA. In actuality, the investigation was more like a trial, with “witnesses” testifying against the ILA and its leadership. Eventually, the highly publicized investigation ended with the condemnation of both the ILA and the beloved Ryan as corrupt. The Waterfront Commission of the New York Harbor was created in 1953 to temporarily oversee the waterfront and was given what many characterized as dictatorial power.

The ILA strove to clean house and rid itself of the few members who had in fact been proven corrupt or criminal, but the Waterfront Commission set forth unattainable goals from the beginning. In August 1953, the ILA was suspended from the American Federation of Labor, a devastating blow. The AFL created the International Brotherhood of Longshoremen (IBL-AFL) to replace the besmirched ILA and scheduled representational elections.

The accusations of negligence which so brutally damaged Ryan’s reputation were ultimately proved to be groundless. Nevertheless, under the relentless pressure of the investigations and denunciations, Ryan resigned. Captain William V. Bradley was elected to the presidency of the ILA-Independent at the November 1953 convention.

1950 TEDDY GLEASON FIGHTS TO SAVE ILA

ILA IN TURMOIL

The IBL Threat

National Labor Relations Board

ILA Victorious in Port of NY

IBL Violence

Teddy Gleason Fights to Save ILA

Demise of the IBL

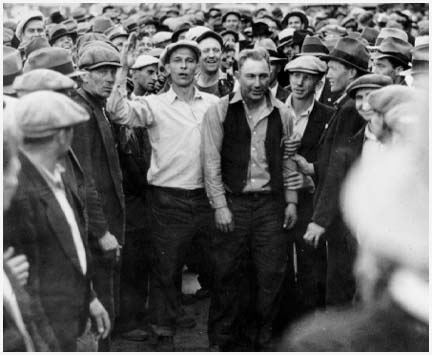

To combat the spread of the carpetbag IBL, the ILA sent Thomas “Teddy” Gleason, ILA General Organizer, from port to port nationwide. The urgency of the task was matched by Gleason’s unremitting ardor. Meanwhile, 17,000 longshoremen voted in the December 23rd and 24th 1953 National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) election to determine representation in the Port of New York. The ILA was victorious, but immediately, Governor Dewey waged a campaign to overturn the election results.

“Many ILA officials could not simply stand by as their men fought on the docks and risked punishment to join the fight. ”

Tension on the New York piers was mounting daily. Staunch ILA loyalists and many other longshormen were at best suspicious and at worst intolerant of the IBL, which they viewed as a machine of the Waterfront Commission and a scab union. By early March 1954, the storm finally hit when Teamster boss David Beck betrayed the ILA by refusing to cross an IBL picket line. News spread and on piers up and down Manhattan, ILA longshoremen refused to touch Teamster deliveries. The cry, “To hell with these scabs, lets hit the bricks” crippled the Port of New York as gangs of longshoremen walked off the docks in a wildcat strike, which spread like wildfire.

A March 4th NLRB injunction forbade ILA leaders from striking or disrupting freight transportation. Many ILA officials could not simply stand by as their men fought on the docks and risked punishment to join the fight. Violence erupted by mid-March as the IBL, facilitated by the police and Beck’s Teamsters, smashed picket line after picket line. On March 18th the NLRB examiner effectively overturned the December elections based on the claim they were conducted “in an atmosphere of terror, coercion, and intimidation.” despite evidence to the contrary. This proved to be the last straw, for less than a week later, Bradley made the ILA strike official. Other unions and workers gave their complete support to the ILA, including a major Teamsters local, which indicated Beck’s opposition to the ILA strikers was not shared throughout the rest of the Teamsters.

The balance of power began to shift as Gleason gained ground against the IBL and longshoremen along the coast refused to handle diverted cargo. Dewey’s anti-ILA entourage responded to the shift with a series of legal actions. Then, on April 4th the NLRB officially set aside the results of the December elections and called for a new vote. The final blow, however, was the NLRB’s announcement that the ILA would be banned from future elections unless it ended the work stoppage “forthwith.” Bradley had no choice but to send his men back to work.

The ILA won a slim victory in the May 26th election, despite aggressive IBL campaigning. In August 1954, the results were finally approved and certified by NLRB and the ILA was given representational rights in the Port of New York. The IBL did not go quietly and forced a third representational election in 1956, in which it was again defeated. By the time an AFL-CIO committee recommended re-admittance for the ILA in August 1959, the IBL was active only in the Great Lakes. In October, the IBL officially dissolved itself and IBL president Larry Long became president of ILA’s Great Lakes District.

1960 TEDDY GLEASON ELECTED PRESIDENT OF THE ILA REBUILDING THE ILA

Teddy Gleason elected president

Longest Lasting ILA Contract

Guaranteed Annual Income

Job Security Program

Rules on Containers

Teddy Gleason was unanimously elected president at the ILA International Convention in 1963. He had always been respected, and the value of his efforts as General Organizer during the troubles of the 1950s was well known. His utter devotion to the union was clear to even the most casual of observers. The delegates who elected Gleason were looking for change, progress, and modernization. Gleason took up this charge and moved the headquarters to its current location at 17 Battery Place, then focused on settling the union’s troubled financial affairs.

“As automation and containerization increased, Gleason’s foresight saved countless jobs.”

In 1965, Gleason negotiated what was at the time, the longest lasting ILA contract in history. It was also the first truly forward-looking contract the union signed. This focus on the future of longshoring in general and the welfare of ILA members was characteristic of Gleason’s twenty-four (24) year tenure as ILA president. As automation and containerization increased, Gleason’s foresight saved countless jobs. Gleason-era initiatives such as the Guaranteed Annual Income (GAI) program, the Job Security Program (JSP) and the “Rules on Containers” (The Rules) have endured, often against bitter opposition, to this day. Under Gleason, the ILA once again became a strong and powerful force in the world of labor.

2000 ILA IN THE PRESENT

“The International Longshoremen’s Association stands ready to meet the challenges of the Twenty-First Century head on.”

The ILA has finally lived up to its bygone leaders’ vision of a modern union-from scholarship programs.to charitable giving through the ILA Children’s Fund.to the ILA Civil Rights Committee’s commitment to advancing social justice.to labor-management cooperation initiatives like the Industry Resources Committee. The International Longshoremen’s Association stands ready to meet the challenges of the Twenty-First Century head on.